America’s Infant Formula Crisis and the ‘Resiliency’ Mirage

Dear Capitolisters,

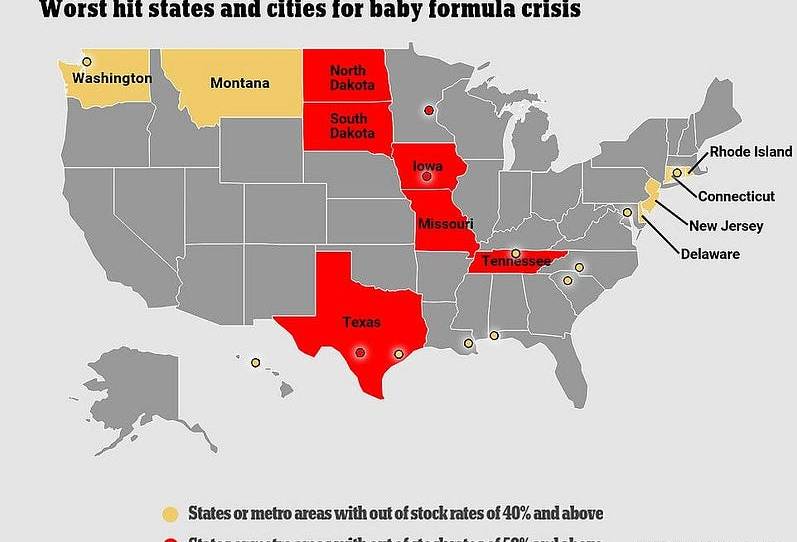

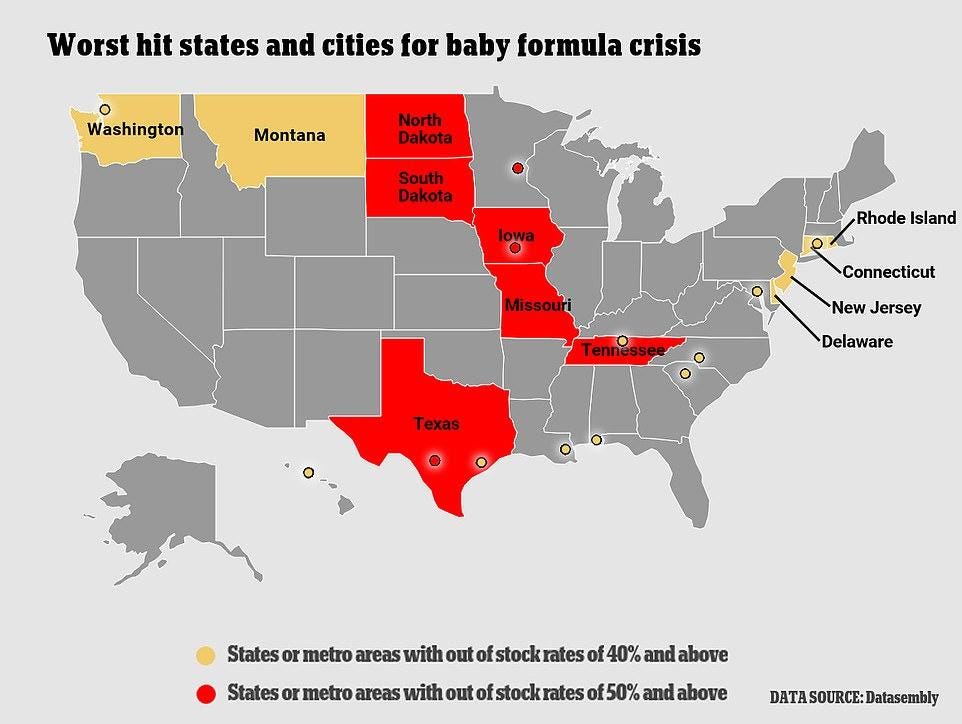

Throughout the pandemic, we’ve ingested a hefty diet of stories on various “crises” that, quite frankly, weren’t really crises at all. I mean, no offense to you gamers out there, but, while limited supplies of PlayStations may very well stink, it ain’t really a “crisis.” (I await your hate mail!) The current situation with infant formula, on the other hand, really does seem quite serious. In particular, a February/March 2022 FDA recall of Abbott Nutrition formula products made at a problematic Michigan facility has pushed an already-stressed U.S. market into full-on panic mode. Not only are supplies desperately short in numerous states, but prices have (as they do when supplies are low) spiked, leaving families—especially ones with low incomes or babies that need special products—in desperate shape.

Retailers are also rationing the stock they do have, in order to deter hoarding by panicked parents. And, while remaining domestic manufacturers are operating flat-out and promising to increase supply as much as possible, they say there’s just so much they can do to quickly solve the problem.

So What’s Going On?

In some ways, the infant formula situation is just another example of the pandemic doing its thing. The Wall Street Journal, for example, reported in January—before the big Abbott recall—that domestic producers were struggling with the same things that almost all U.S. manufacturers are struggling with: labor and materials shortages, transportation and logistics hiccups, and erratic demand. The demand issue may be particularly severe for baby formula:

Laura Modi, co-founder of Bobbie, an online organic baby-formula startup, said even intermittent shortages can lead parents to stockpile. She said her company has seen an influx of demand from parents rattled by the lack of availability of big-name formula brands. “It can take one post in a Facebook moms group to send some into a panic,” she said.

Any parent who’s used formula (including this one) can surely relate. Unlike most other COVID-19 panics, there often aren’t good alternatives for the formula your baby can consume. So when you start seeing those shelves get bare … it’s crisis mode, for sure. And then came the FDA recall, which affected a substantial chunk of domestic supply, to throw even more fuel on the fire.

No wonder parents are stressed.

It’s Not Just the Pandemic

Unfortunately, the infant formula crisis isn’t simply another case of a one-off event causing pandemic-related supply chain pressures to boil over. Instead, U.S. policy has exacerbated the nation’s infant formula problem by depressing potential supply. First, as my Cato colleague Gabby Beaumont-Smith just documented, the United States maintains high tariff barriers to imports of formula from other nations—all part of our government’s longstanding subsidization and protection of the politically powerful U.S. dairy industry. Imports of formula from most places, such as the European Union, are subject to a complex system of “tariff rate quotas,” under which already-high tariffs (usually 17.5 percent, but it depends on the product) increase even further once a certain quantity threshold is hit.

We even restrict imports of formula from most “free trade” (scare quotes intended!) agreement partners, including major dairy producing nations like Canada. In fact, a key provision of the renegotiated NAFTA—the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA)—actually tightened restrictions on Canadian baby formula to ensure that new investments in Ontario production capacity by Chinese company Feihe would never threaten the U.S. market:

Canada agreed that, in the first year after the agreement takes hold, it can export a maximum 13,333 tonnes of formula without penalty. In USMCA’s second year, that threshold rises to 40,000 tonnes, and increases only 1.2 per cent annually after that. Each kilogram of product Canada exports beyond those limits gets hit with an export charge of $4.25, significantly increasing product costs….

Canada wanted to attract investment for a baby formula facility because it uses skim milk from cows as an ingredient. Healthy consumer appetites for butter leave provincial milk marketing boards with a surplus of skim. Baby formula looked like a smart use for it, and Canada didn’t have any significant infant formula production before Feihe arrived.

Expanding this plant, or building a second infant formula plant somewhere else in Canada, look like less attractive business propositions under this new trade deal.

The bolded part is especially important today: Because USMCA effectively capped possible exports of infant formula to the United States, it discouraged investment in new Canadian capacity—capacity that we sure could use right now. The same goes for other potential Canadian suppliers—indeed, that’s the whole point of the USMCA restrictions. As Big Dairy’s trade associations stated in supportive public comments after the agreement’s text was completed:

A particularly critical additional element of USMCA in this area is the export surcharge that is intended to discourage exports of Canadian SMP, MPC and infant formula beyond specified quantities. Properly administered, this provision will be an essential tool in constraining Canada’s ability to dump unlimited quantities of dairy products onto global markets…. Canada must ensure that these surcharges function as intended to discipline the export expansion of these product areas.”

Export expansion! Heaven forbid!

If tariffs were the only problem here, then high prices in the United States right now might induce alternative supplies from overseas producers looking for new customers and profits. Unfortunately, however, the United States also imposes significant “non-tariff barriers” on all imports of infant formula. Most notable are strict FDA labeling and nutritional standards that any formula producer wishing to sell here must meet. Aspiring manufacturers also must register with the agency at least 90 days in advance and undergo an initial FDA inspection and then annual inspections thereafter. And the FDA maintains a long “Red List” of non-compliant products that are subject to immediate detention upon arriving on our shores. As a result, the FDA routinely issues notices that it has seized “illegal” (e.g., improperly labeled) infant formula from overseas:

The FDA has also forced foreign distributors to recall products sold via third party websites:

Following this recall in particular, FDA seizures of this illegal product (sigh) reportedly increased.

Key here is the European Union, which is the world’s largest producer and exporter of infant formula, especially in the Netherlands, France, Ireland, and Germany. (China, it must be noted, produces a lot of formula but sells almost all of that to its domestic market.) European formula also has been found to meet FDA nutritional requirements, and is in high demand by some American consumers. Yet, when parents here have tried to import European formula, it’s been routinely subject to seizure by the FDA. In fact, formula made by two of the most popular European brands—HiPP and Holle—is on the FDA’s red list and thus only arrives here via unofficial, third party channels.

Unless the FDA gets to it first.

These regulatory barriers are probably well-intentioned, but that doesn’t make them any less misguided—especially for places like Europe, Canada, or New Zealand that have large dairy industries and strict food regulations. Indeed, as the New York Times noted about “illegal” European formula in 2019, “food safety standards for products sold in the European Union are stricter than those imposed by the F.D.A.” And, it must be noted, it was an unsanitary American factory that fueled our current crisis, and the FDA may have even ignored a whistleblower’s complaints about the situation “months before infant formula was removed from grocery store shelves.”

So spare me the “unsafe imports” stuff, okay?

Finally, Beaumont-Smith notes that another U.S. regulatory barrier—“marketing orders” for milk products—might also be discouraging imports or stifling American production:

These laws cover multiple classes of milk and establish a system for dairy farmers with price and income supports, and trade barriers. The milkiness (ha) of the system makes it difficult to clearly conclude that these orders impact infant formula but given dry milk is a vital component, it can be inferred that these orders … distort economic activity in the dairy sector that could stymie U.S. producers’ ability to produce more formula to help make up for lost supply. And of course, the import barriers contained within the orders dampen U.S. producers’ demand for foreign classes of milk, including dry milk, thereby reducing options, which are needed most during domestic emergencies.

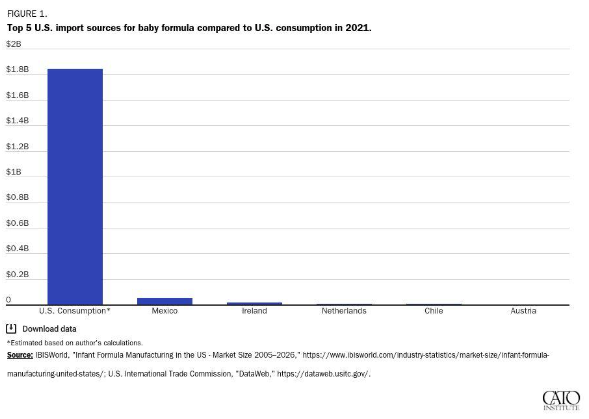

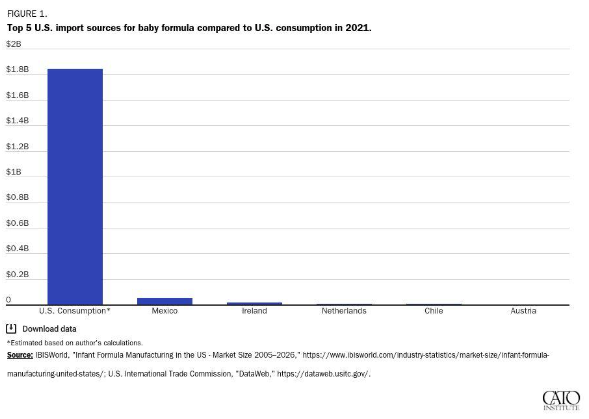

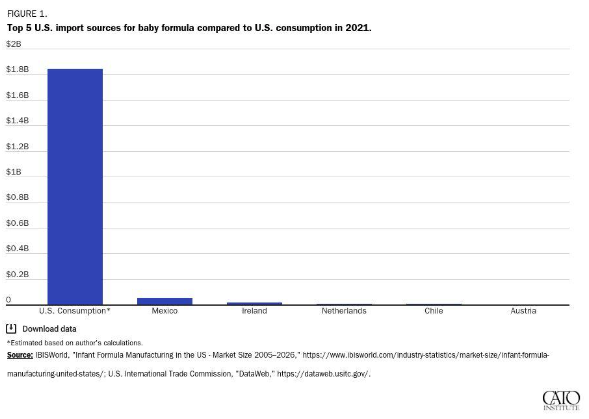

The combination of trade and regulatory barriers to imported infant formula all but ensures that our almost $2 billion U.S. market is effectively captured by a few domestic producers—despite strong demand for foreign brands. What German company, for example, is willing to spend the time and money meeting all the FDA requirements—registration, clinical trials, labeling and nutritional standards, inspections, etc.—only to then face high import taxes that make its product uncompetitive except during emergencies? The answer: almost none.

Tellingly, the country facing the lowest U.S. trade barriers, Mexico, is also the largest foreign supplier of infant formula, while powerhouse European suppliers barely register. Meanwhile, Abbott is in full-on crisis mode and has turned to flying in formula produced at an FDA-registered Irish affiliate:

Abbott, based in the US, has turned to its staff at Cootehill, Co Cavan, and the 1,000 dairy farms supplying ingredients to the plant.

The company said the plant is registered by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and it has increased the volume of Similac Advance powder formula produced in Cootehill, for daily air-shipping into the US. “This year, we’ll more than triple the Similac Advance powder formula we import from our Cootehill, Ireland manufacturing site,” said a spokesperson.

Those (highly tariffed) Irish imports will surely disappear once the U.S. crisis subsides. Nevertheless, both they and Mexico’s volumes are a testament to the potential benefits of broader U.S. liberalization of trade in infant formula.

Maybe somebody could inform Congress.

But Wait, There’s (Unfortunately) More

Compounding issues in the U.S. market is the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children program (called “WIC”), which provides vouchers for low-income Americans (at or below 185 percent of the poverty line) to buy formula at approved retailers. According to the USDA, which administers WIC, the program served about 1.5 million infants in 2021 (for context, there were about 3.6 million total births that year). Various reports estimate that WIC sales constitute about half of all infant formula sales in the United States.

Giving taxpayer money to poor American babies isn’t objectionable (even to this libertarian!), but WIC’s design raises some serious concerns. Here’s how it works:

Since 1989, State WIC Agencies have been required to enter sole-source contracts for infant formula. Under these contracts, the over 1.2 million infants served by WIC are limited to specific brands of “contract formula” that are eligible for discounted rebates from infant formula manufacturers, reducing overall program costs. Abbott Nutrition contracts with the majority of State WIC Agencies.

As the Wall Street Journal explained a few years ago, the discounts provided are very significant:

Fierce bidding for those state contracts has led the three biggest formula makers to offer steadily deeper discounts—on average 92% below wholesale prices—eroding profits on WIC sales. But winning a state’s contract makes a formula maker the dominant player on a state’s grocery store shelves, where the companies try to make up for their money-losing WIC sales.

Given these steep discounts, WIC is undoubtedly a good deal for U.S. taxpayers and WIC customers—in normal times, at least. Now, however, the program may be contributing to the current crisis in at least three ways. First, as the dominant buyer of infant formula in the United States and by demanding below-market contract prices, WIC may discourage additional investments in U.S. capacity or new market entrants. Put simply, nobody had an incentive to break into the U.S. infant formula market—or to boost existing U.S. production—when half of the market is effectively controlled by a single buyer demanding unprofitable prices and compliance with piles of state and federal regulations. As one expert put it years ago about WIC, the government “is using its monopsony power to extract an involuntary program subsidy from an industry.” That’s not exactly a great way to encourage more domestic investment or supplier diversity, especially when—as National Review’s Dominic Pino documented yesterday—the major producers have alternatives:

The major baby-formula makers do business in many other markets as well, so it’s hard for them to justify continuing to lose money on steeply discounted government-contracted baby formula when they could focus their efforts elsewhere. Reckitt Benckiser, for example, also owns Lysol, Mucinex, and Durex, among many other brands, and it’s currently trying to sell its baby-formula division — or, what’s left of it, since it already sold the Chinese portion of that division last year.

Second, WIC distorts domestic price signals and thus discourages new production from coming online when supply gets tight. Pino again:

In a free market, widespread shortages shouldn’t occur. The price should rise as supply gets low, which encourages more production. The increased production should prevent a prolonged shortage before it has a chance to get started, then bring the price back down as well….

With government responsible for over half of the country’s baby-formula purchases, price signals don’t work like they should. As research firm Datasembly noted, the baby-formula market was beginning to go awry before the Abbott recall. The out-of-stock percentage moved from its normal range into double digits in July of last year. Yet “overall prices didn’t increase when out-of-stock percentages started to increase,” it found.

Such behavior would be very strange in a free market, but it makes perfect sense when you consider that predetermined contracts with state governments are responsible for such a large segment of total purchases. The USDA is fully aware of these problems, noting in a 2015 article that “WIC essentially replaces price-sensitive consumers of infant formula with price-insensitive consumers.” A 2015 USDA report finds that lack of price sensitivity also contributes to the long-term increase in baby-formula prices, as both manufacturers and retailers have steadily raised their prices above the overall rate of inflation for years. We don’t get short-term price increases when they would help prevent shortages, but we do get long-term price increases that slowly make formula less and less affordable — which further encourages WIC expansion.

WIC expansion, yes. But not, unfortunately, the expansion of domestic infant formula production.

Finally, the WIC program’s use of sole supplier contracts has created a problem specific to the current crisis because, as noted above, the big FDA recall just happened to hit the very producer—Abbott—holding most of the WIC contracts. So we have tons of WIC customers forced to find other options and therefore added stress on the U.S. market:

The USDA granted a temporary waiver for WIC clients to obtain alternative brand options of baby formula, further compounding the supply chain issues as a new pool of parents are now vying for what was already a limited supply of products.

Research also shows that the WIC-winning manufacturer ends up getting a major boost in the U.S. market generally:

[T]he manufacturer holding the WIC contract brand accounted for the vast majority–84 percent–of all formula sold by the top three manufacturers. The impact of a switch in the manufacturer that holds the WIC contract was considerable. The market share of the manufacturer of the new WIC contract brand increased by an average 74 percentage points after winning the contract. Most of this increase was a direct effect of WIC recipients switching to the new WIC contract brand. However, manufacturers also realized a spillover effect from winning the WIC contract whereby sales of formula purchased outside of the program also increased.

This means that WIC made the very U.S. manufacturer now in trouble with the FDA, Abbott, the dominant national supplier, with predictable effects for the domestic market when Abbott’s Michigan factory shut down. Abbott and the other U.S. producers will surely try to fill the breach until that facility comes back online, but—given Abbott’s problems and tightness in U.S. labor and materials markets generally, as well as the fact that the other formula companies weren’t expecting demand for their products (in part due to WIC!)—it’s unclear whether quick capacity expansion is possible.

For American families’ sake, let’s hope things clear up soon.

Summing It All Up

Bad U.S. policy surely didn’t cause the infant formula crisis, but it just as surely made the situation worse than it needed to be. Trade barriers and poorly designed welfare policies helped create a brittle system dominated by a few domestic players—a system that might muddle through in the good times but one that crumbles in the face of a serious shock and struggles to recover thereafter. Meanwhile, American consumers (here, babies and their already frazzled parents) are left in the lurch, and world-class foreign producers can’t help much because they lack the necessary paperwork and financial incentives or because past U.S. policies have discouraged them from setting up official distribution channels or new facilities to serve the American market.

Given market realities, it seems unlikely that U.S. policymakers can flip some policy switch and quickly fix the situation, but they can at least (hopefully) learn a few lessons.

First, the infant formula situation is an unfortunate reminder that the trendy economic nationalist policies proposed to make America more “resilient”—tariffs, localization mandates, government contracts, etc.—can actually make us weaker by discouraging global capacity, supplier diversity, and system-wide flexibility. As I’ve said a million times now, reshoring supply chains might insulate us from external supply and demand shocks, but it also can amplify domestic shocks (and reduce overall economic growth and output to boot). We’re seeing that reality play out once again in the highly protected and regulated U.S. dairy market, where domestic production accounts for the vast majority of American consumption. Indeed, infant formula—with its protectionism, regulations, and heavy dose of government direction—is pretty much the poster child for what nationalist “industrial policy” advocates today propose for all sorts of “strategic” industries. And, well… here we are. Lessons abound.

Second, the formula crisis points to a better way forward for U.S. policy. Most obviously, the United States should follow the lead of major dairy producing nations Australia and New Zealand and eliminate barriers to imported infant formula and other dairy products—for practical/economic reasons and for moral ones. (Taxing baby formula to enrich Big Dairy?! COME ON.) The United States also should embrace—as we discussed previously for rapid tests—a regulatory system that allows Americans to buy any food approved by the FDA or any other competent regulator. If it’s good enough for consumers in Europe, Canada, New Zealand, Australia, Japan, etc., it’s good enough for us (and if some folks still want to buy American, nothing’s stopping them). Finally, the WIC program should probably be overhauled to ensure that the system doesn’t short-circuit price signals and supplies. Replacing the convoluted and distortionary sole-supplier bidding/contract approach with a simple cash voucher for qualified parents would be the obvious place to start, especially when paired with pro-consumer trade and regulatory reforms that would lower formula prices generally. (And when we’re done doing that, we should embrace a host of other market-oriented policies that will help American moms.)

These changes won’t put formula on American store shelves tomorrow—and they might not be good for the economic nationalists or Big Dairy—but they’d definitely be better for the rest of us in the longer term. It’s too bad parents had to learn this lesson the hard way.

Chart(s) of the Week

Seattle’s minimum wage depressed hours and entrants:

People don’t seem psyched to go back to the office:

The Links

In which I offer five market-oriented policies to help U.S. semiconductor manufacturing

Relatedly, the former head of TSMC pours cold water on U.S. industrial policy plans

More foreign-invested automobile manufacturing coming to the Sun Belt

Meanwhile, US Steel is using its tariff windfall to finance a move South—and away from unions

Libs ask: seriously why hasn’t Biden lifted the tariffs?

It’s a (small) start: Biden suspends “national security” tariffs on Ukrainian steel

CIA director: Russia may have changed China’s Taiwan calculations

“China’s economy is going backwards”

China’s top two leaders publicly disagree about COVID strategy

Canadian retailer replaces in-store cashiers with kiosks and… Nicaraguans

“Let’s Make Being a Mom Easier (For Once)”

Trade remedy investigation of solar imports causing big economic (and political) problems

China’s troubles are another hit to America’s eternal pessimists

Bootleggers and Baptists, Canadian hydropower edition

U.S. vaping regulations discourage menthol smokers from switching to smokeless alternatives